When the stars were our teacher

A multi-generational poetic map of the heavens![]()

“From Zeus let us begin, him do we mortals never leave unnamed, full of Zeus are all the streets and all the market-places of men, full is the sea and the havens thereof, always we all have need of Zeus.”

Aratus of Soli, C3rdBCAs far back as our recorded human history permits us to see, women and men — through making — have been shaping material and immaterial realities. The cosmos within which our ancestors inhabited was a realm full meaning and values, (which they nurtured). Ultimately, stories became carrier of sacred information holding people morally and emotionally accountable for their actions. Enacting and re-enacting those stories both in the material and immaterial world allowed for the codification of rules helping people maintain a sense of belonging to their own culture and to the universe. From widespread bear imagery and ceremonialism among boreal cultures of Eurasia, to the codified drawn patterns inherent to cultures of the South Pacific. As a species, we developed a particular talent for rationalizing abstract information in order to define its formal correspondence across multiple mediums, may that be rock carving, weaving, dancing, or tattooing.

The Aratean creative format

![]()

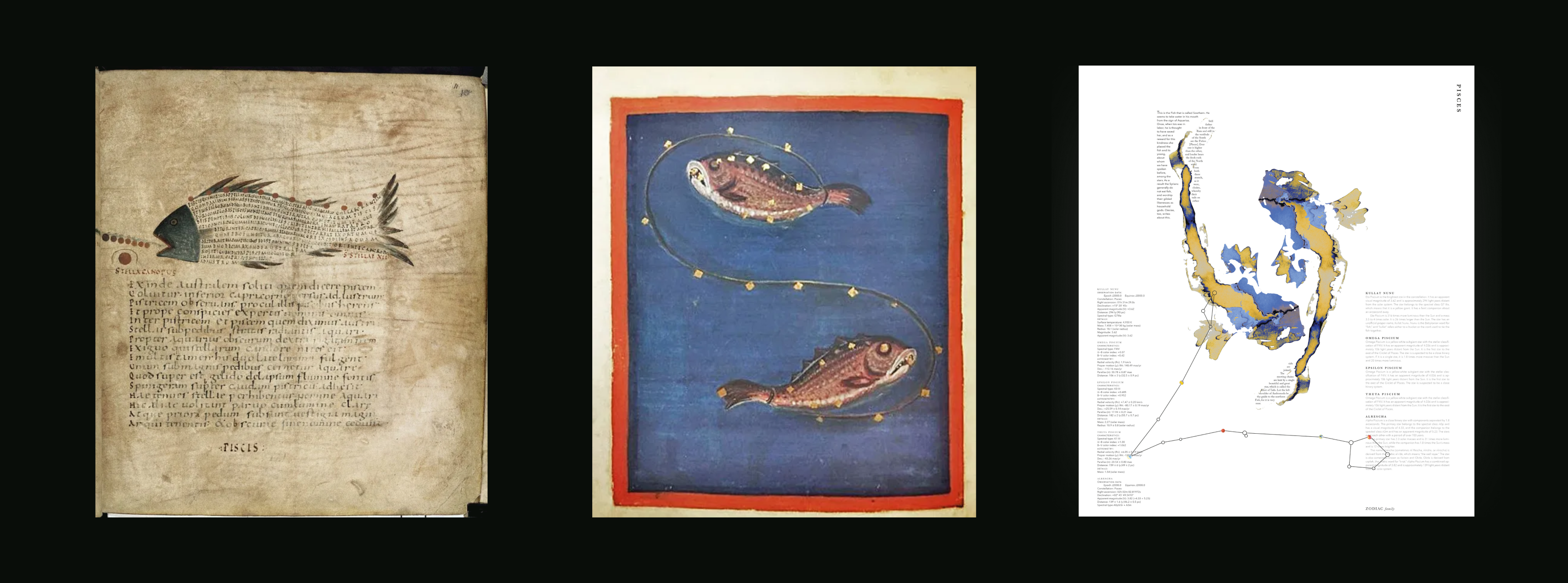

From left to right, Pisces — Harleian Manuscripts, Pisces — Leiden Aratea, Pisces — Constantin Aratea

From left to right, Pisces — Harleian Manuscripts, Pisces — Leiden Aratea, Pisces — Constantin Aratea

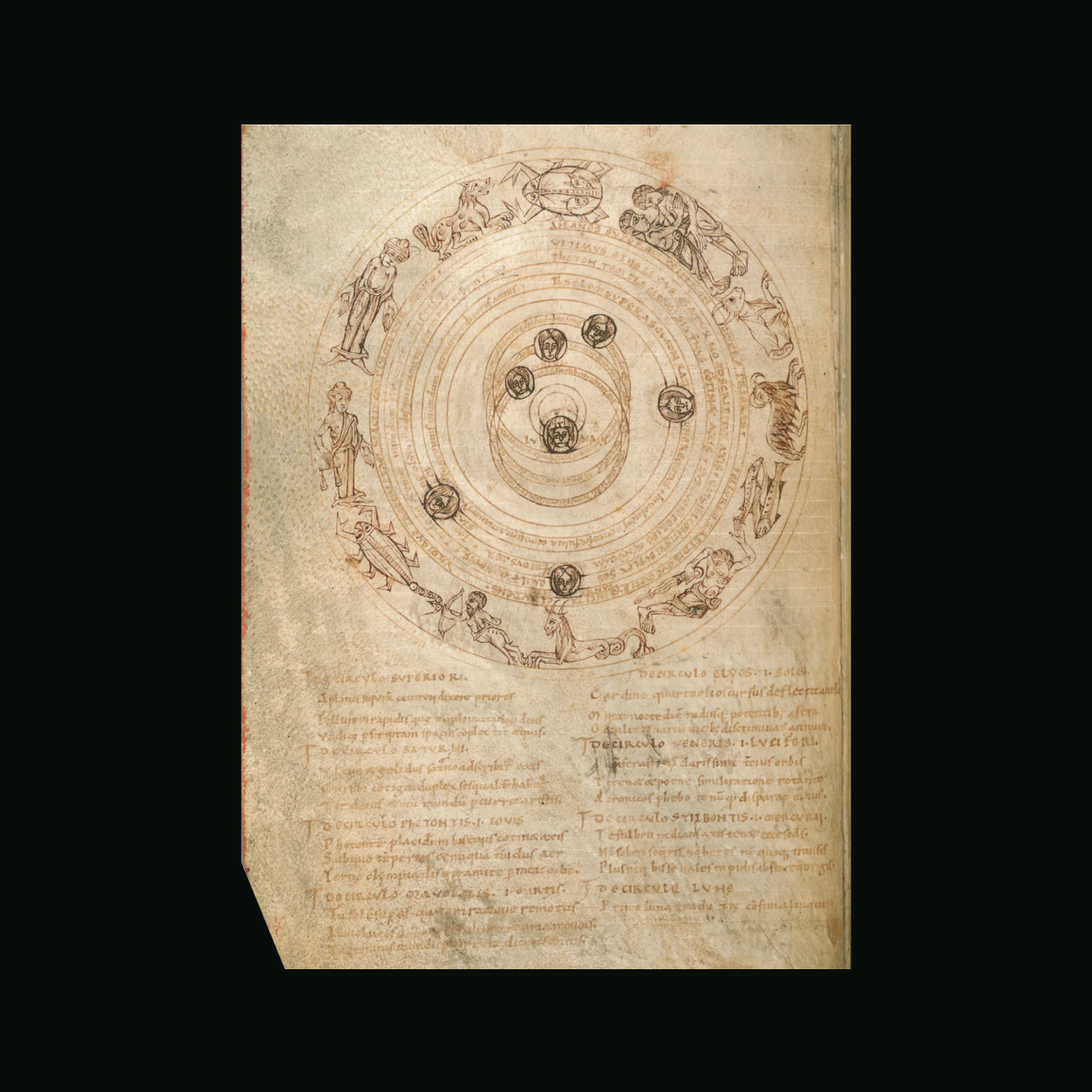

The Aratean creative format is distinguished by its unique blend of poetic narration and scientific description. It functions as an evolving textual and visual tradition that allows successive generations to reinterpret and expand upon its content.

This approach uncompromisingly presents the lineage of creative influences, crystallizing the meta-structure of any artistic or intellectual legacy over time. At its core, the Aratean creative format integrates hand-written verses with visual elements, creating a format where artistic expression and scientific accuracy coexist. This format supports both textual revisions and graphical reinterpretations, making it a dynamic medium for transmitting knowledge.

“The Aratean tradition exemplifies how knowledge, myth, and science can intertwine across millennia, continuously reshaped by those who seek to understand and reinterpret the world they live in.”

This approach uncompromisingly presents the lineage of creative influences, crystallizing the meta-structure of any artistic or intellectual legacy over time. At its core, the Aratean creative format integrates hand-written verses with visual elements, creating a format where artistic expression and scientific accuracy coexist. This format supports both textual revisions and graphical reinterpretations, making it a dynamic medium for transmitting knowledge.

Constantin’s Aratea

![]()

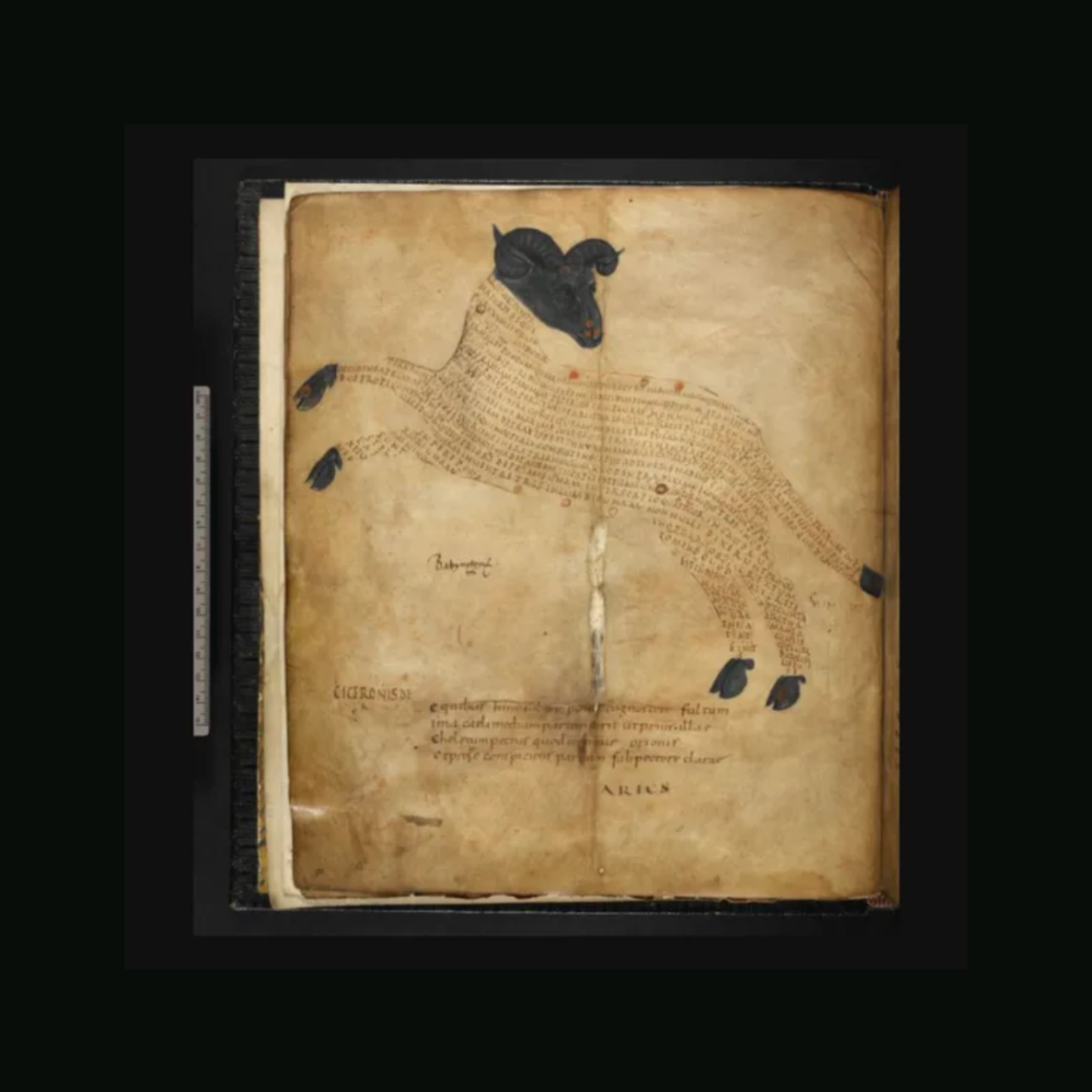

Aratea, Northern France circa 820. Harleian Manuscripts, propriety of the British Library

![]() Aratea, Northern France circa 820. Harleian Manuscripts, propriety of the British Library

Aratea, Northern France circa 820. Harleian Manuscripts, propriety of the British Library

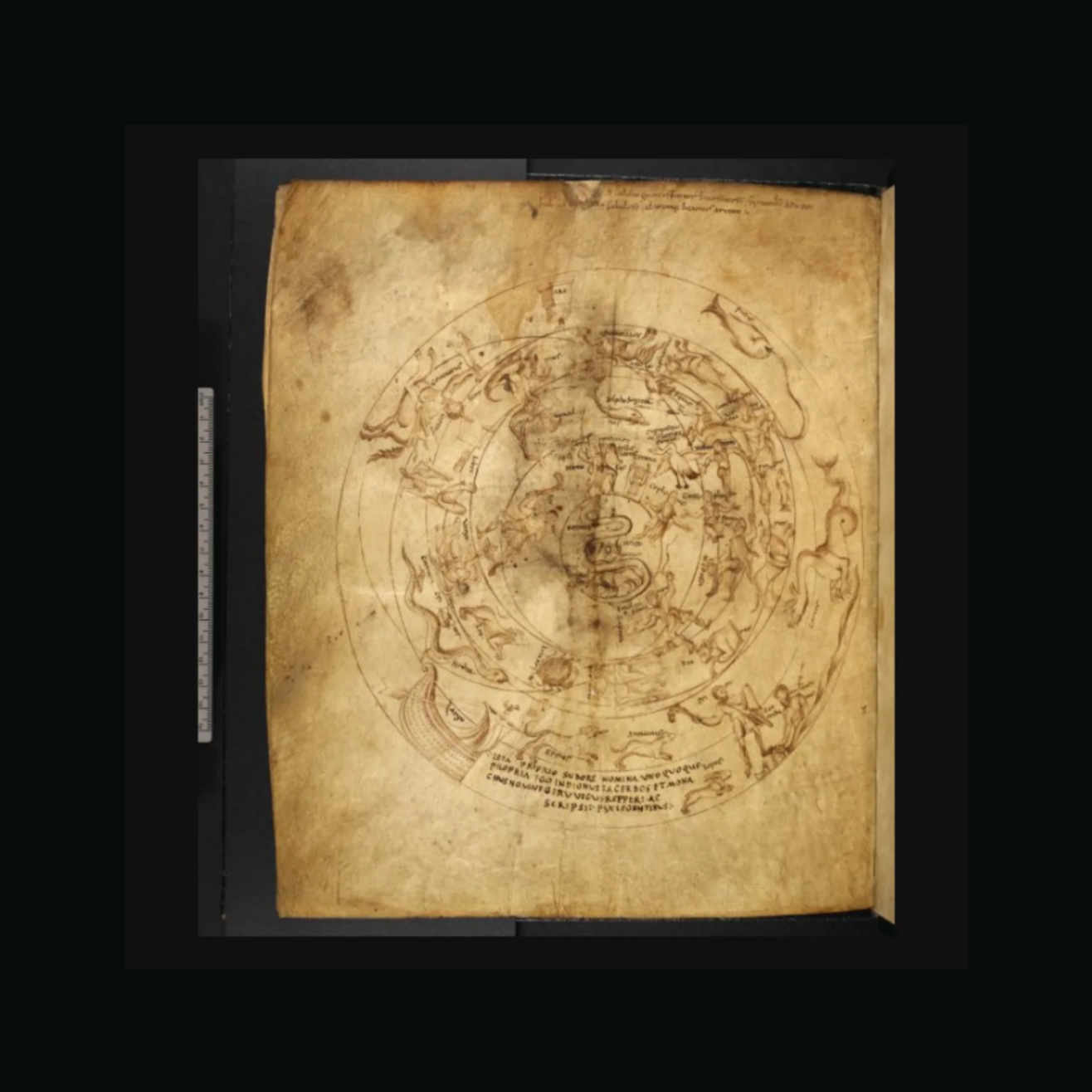

![]() The Aratea of Germanicus — Map of the heavens. Medieval Astronomy from around 1000AD

The Aratea of Germanicus — Map of the heavens. Medieval Astronomy from around 1000AD![]()

Constantin’s Aratea — Centaurus. 2016, Cambridge

Aratea, Northern France circa 820. Harleian Manuscripts, propriety of the British Library

Aratea, Northern France circa 820. Harleian Manuscripts, propriety of the British Library

Aratea, Northern France circa 820. Harleian Manuscripts, propriety of the British Library The Aratea of Germanicus — Map of the heavens. Medieval Astronomy from around 1000AD

The Aratea of Germanicus — Map of the heavens. Medieval Astronomy from around 1000AD

Constantin’s Aratea — Centaurus. 2016, Cambridge

Several years ago, I stumbled upon a series of images depicting the work of Roman statesman, politician, and philosopher Marcus Tullius Cicero. While Cicero was infamous for his oratory skills in the senate, which led him to being executed while declared enemy of the state by Marc Anthony in 43BC — at the young age of 23 — the man had produced a ‘revival’ of an ancient didactic and poetic map of the heavens titled Phaenomena.

Originally attributed to a young greek poet named Aratus of Soli (C3rd BC), his only surviving work; Phaenomena — a book aiming at describing the constellations and weather signs — used didactic poetry as a medium to communicate practical information. Writing his poem at the request of ruler of Macedonia Antigonus Gonata (320–239BC), Aratus derived his entire description of the heavens not from his observations of the skies themselves but from a celestial globe on which constellation outlines had been drawn by astronomer Eudoxus of Cnido (circa 390–340BC). Adopting from Eudoxus the entire detailed arrangement of the globe and describing it in verse— for the next hundred of years, Aratea’s Phaenomena served as a framework for various ancient poets and scholars.

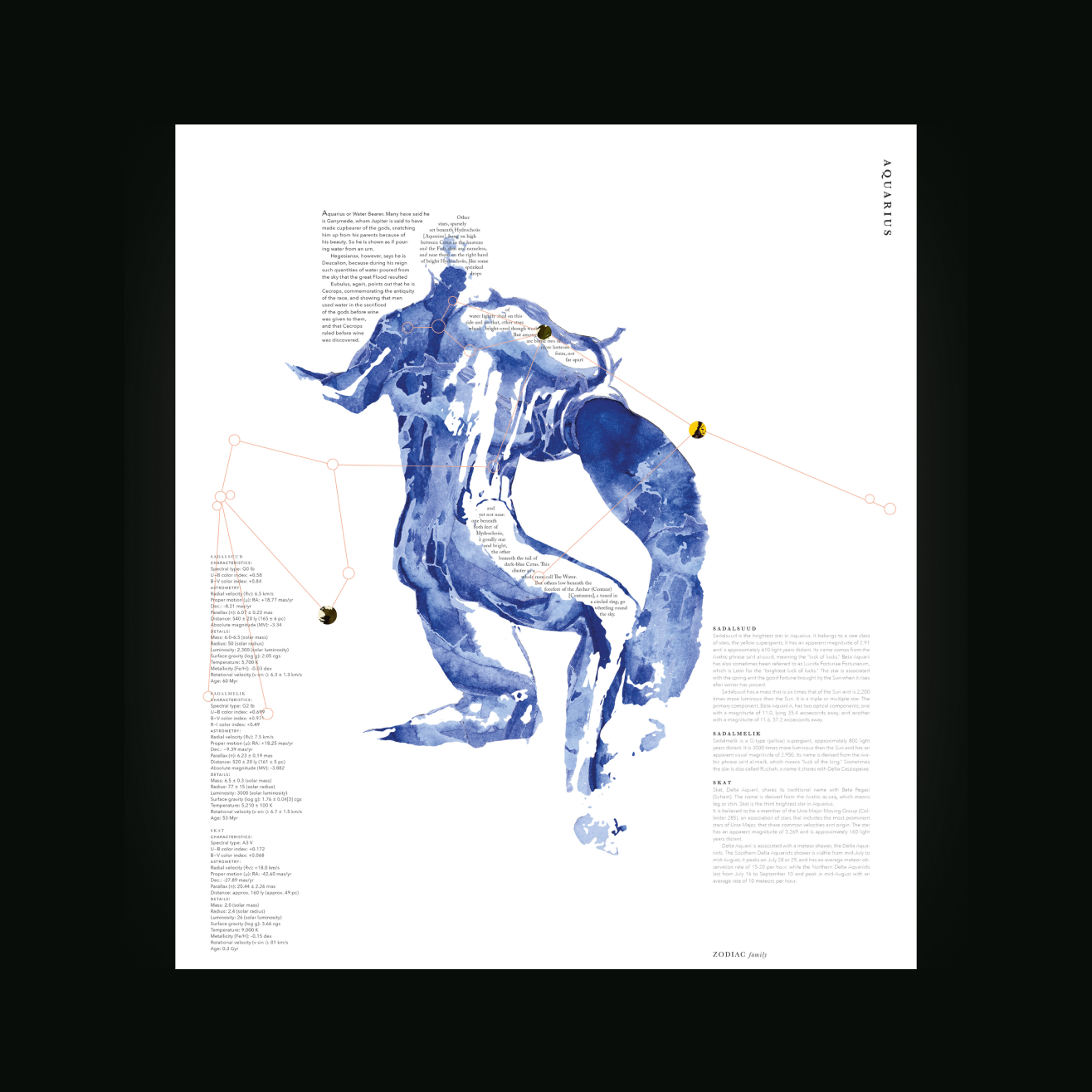

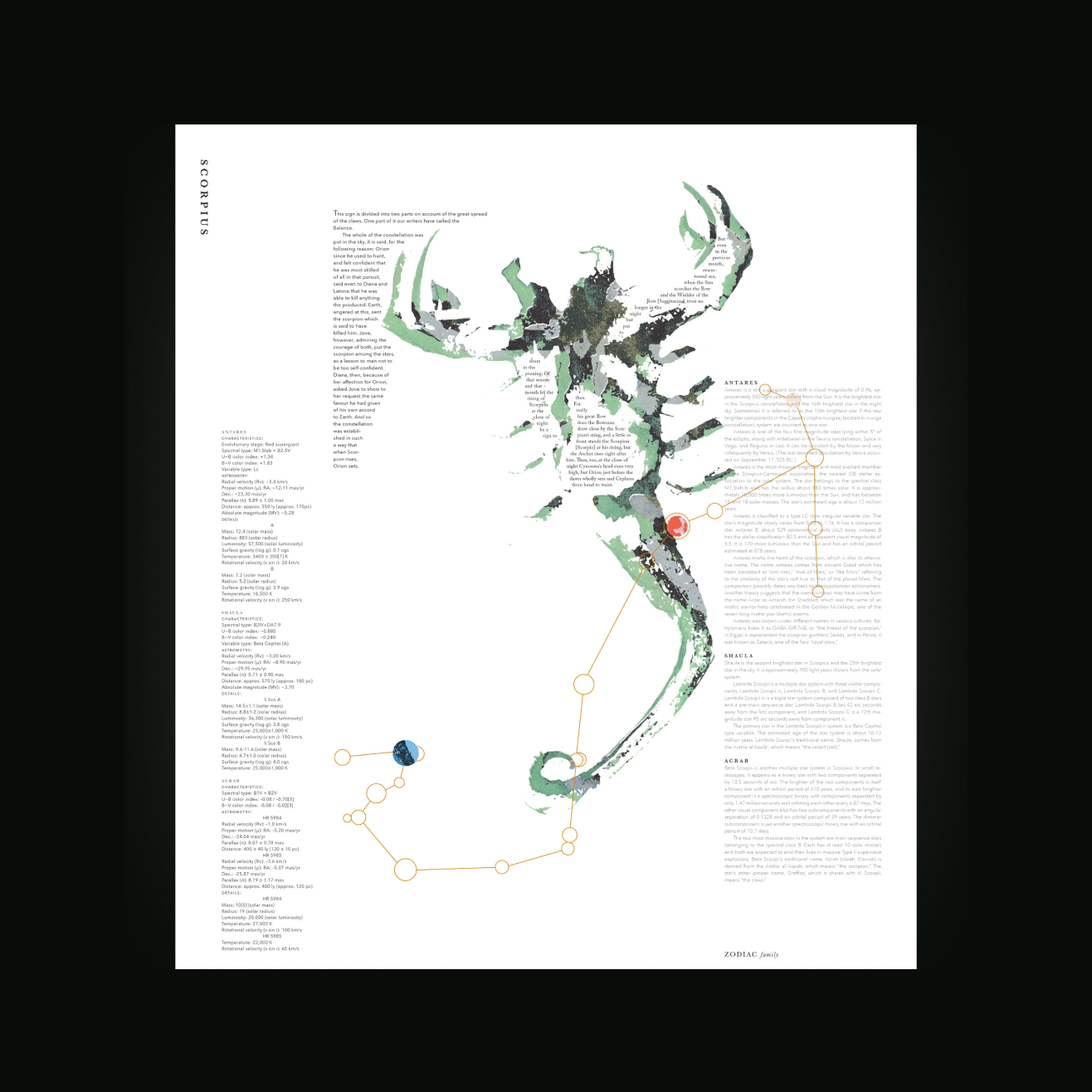

Relative to the period the information inherent to Phaenomena was shaped and shared, this multi-generational poetic map of the heavens — as a concept — could be used as a point of reference for contemporary creators who aim at furthering and evolving timeless notions and ideas. Tempted by the thought that I could also contribute to this creative odyssey, in a true Aratean Fashion, I curated ancient (pertaining to Aratus and Cicero’ work) and modern (Nasa’s) resources to update our understanding of the heavens, combining both mythological, and scientific thinking. As the visuals attests, my intention was not to offer a pale copy of what had been done before me — rather referencing key formal and conceptual qualities while updating antiquated information.

The literary format inherent to the Aratea produced countless versions and adaptations of the latter and its content. Generation after generation, from the classical world, to the middle ages, to contemporary times — the work of scholars, scientists, and artists contributed to the expansion of this system of thinking, and making. Bound to the same original concept of Informative Poetry, the produced artifacts such as compounded treatise or individual illustrations, act as inter-chronologically connected units defining the Aratean system. By evolving the concept of Tokenization (being assigned unique identification codes and metadata that distinguish them from other units), distinctive and traceable non-fungible tokens can programmatically reveal the generational relationship that exists between one artifact to the next. Uncompromisingly presenting what had come first, and what followed, crystallizing the meta-structure of any creative legacy for eternity.

Originally attributed to a young greek poet named Aratus of Soli (C3rd BC), his only surviving work; Phaenomena — a book aiming at describing the constellations and weather signs — used didactic poetry as a medium to communicate practical information. Writing his poem at the request of ruler of Macedonia Antigonus Gonata (320–239BC), Aratus derived his entire description of the heavens not from his observations of the skies themselves but from a celestial globe on which constellation outlines had been drawn by astronomer Eudoxus of Cnido (circa 390–340BC). Adopting from Eudoxus the entire detailed arrangement of the globe and describing it in verse— for the next hundred of years, Aratea’s Phaenomena served as a framework for various ancient poets and scholars.

This framework, where hand-written verses are combined with illustrations in order to construct forms, shapes, and figures, allowed for the integration of new tools and creative approaches as a mean to update past notions and periodically disseminating knowledge and wisdom to people. In 106BC, Marcus Tullius Cicero translated Aratus’ work from Greek to Latin, greatly influencing thinkers throughout the middle ages who also sought to prolong this creative legacy. In fine, one of the most important Latin versions of Aratus’ poem was made by a writer known as Germanicus, who corrected some of the astronomical errors in the original and changed the orientation of the constellation figures from those on a globe to those in the sky.

“This framework, where hand-written verses are combined with illustrations in order to construct forms, shapes, and figures, allowed for the integration of new tools and creative approaches as a mean to update past notions and periodically disseminating knowledge.”

Relative to the period the information inherent to Phaenomena was shaped and shared, this multi-generational poetic map of the heavens — as a concept — could be used as a point of reference for contemporary creators who aim at furthering and evolving timeless notions and ideas. Tempted by the thought that I could also contribute to this creative odyssey, in a true Aratean Fashion, I curated ancient (pertaining to Aratus and Cicero’ work) and modern (Nasa’s) resources to update our understanding of the heavens, combining both mythological, and scientific thinking. As the visuals attests, my intention was not to offer a pale copy of what had been done before me — rather referencing key formal and conceptual qualities while updating antiquated information.

The literary format inherent to the Aratea produced countless versions and adaptations of the latter and its content. Generation after generation, from the classical world, to the middle ages, to contemporary times — the work of scholars, scientists, and artists contributed to the expansion of this system of thinking, and making. Bound to the same original concept of Informative Poetry, the produced artifacts such as compounded treatise or individual illustrations, act as inter-chronologically connected units defining the Aratean system. By evolving the concept of Tokenization (being assigned unique identification codes and metadata that distinguish them from other units), distinctive and traceable non-fungible tokens can programmatically reveal the generational relationship that exists between one artifact to the next. Uncompromisingly presenting what had come first, and what followed, crystallizing the meta-structure of any creative legacy for eternity.

Thoughts

By crystallizing and perpetuating the meta-structure of stories and creative legacies, this creative format is an invitation to focus on the creation of artefacts of substance. Medium-agnostic works of creativity whose value can be appraised via three distinct axis.

As final words, I hope the reader sees in this format an invitation to think and to make in a way that does not trivialize those very gifts. This opportunity to organize our experiences in the world by creating, and speaking at will — updating our pre-conceived notions is a miracle. Consequently, as some of us leverage new mechanics of the paradigm-shifting technologies — lets keep in mind: as I create, what legacy am I furthering? What thought, or idea, or concept am I updating? More importantly what am I/we to learn from this process?

- Does it augment the transformation and dissemination of knowledge?

- Does it amplify the presence of timeless concepts and ideas in the collective imagination?

- Does it facilitate the discovery of new mediums and creative processes?

While the notion of substance begets a longer conversation, I would argue that any things that directly pertain either to one of the many facets of our personality as a species such as: love, hate, temperance… or one of the many constructed concepts we use to look at the world chaos, order, logic… are worthy candidates.

As final words, I hope the reader sees in this format an invitation to think and to make in a way that does not trivialize those very gifts. This opportunity to organize our experiences in the world by creating, and speaking at will — updating our pre-conceived notions is a miracle. Consequently, as some of us leverage new mechanics of the paradigm-shifting technologies — lets keep in mind: as I create, what legacy am I furthering? What thought, or idea, or concept am I updating? More importantly what am I/we to learn from this process?